By Ainsley Mutrie | December 1, 2025

On Oct 2nd, community members in Armstrong joined Dr. Catherine Tarasoff and the ISCBC Okanagan team to learn about invasive yellow flag iris. The workshop took place on Meighan Creek, where a small infestation of yellow flag iris threatened to spread downstream into the Armstrong Wetlands, a site of a significant community restoration project.

This small but engaged group learned about the characteristics, impacts, and management techniques of yellow flag iris. Yellow flag iris is an aquatic invasive plant that impacts wetlands, ponds, streams and other aquatic ecosystems. It can outcompete native plants and clog waterways, creating thick mats of roots and vegetation that prevent water flow. This affects water quality and ecosystem health by reducing photosynthesis and oxygen levels, increasing sedimentation, rerouting stream flow, and reducing biodiversity.

Dr. Catherine Tarasoff, a restoration leader and friend of the Council, has dedicated over 12 years of research to developing yellow flag iris management techniques, pioneering the benthic barrier method demonstrated and implemented at the workshop. Yellow flag iris spreads both by seeds, which float and disperse downstream, and by an extensive root system. Severing roots or digging up plants can spread fragments that can sprout new infestations, making mechanical removal difficult and often ineffective.

After years of trial and error, Dr. Tarasoff developed a smothering technique that uses a thick mat called a benthic barrier. When installed correctly, this barrier prevents sunlight and resources from reaching the plant, depleting its internal reserves and preventing the plant from returning after one or two years. This technique has been vital for managing yellow flag iris in sensitive ecosystems across the province. It has also shown promise for use on other difficult-to-control species, including reed canary grass and Japanese knotweed.

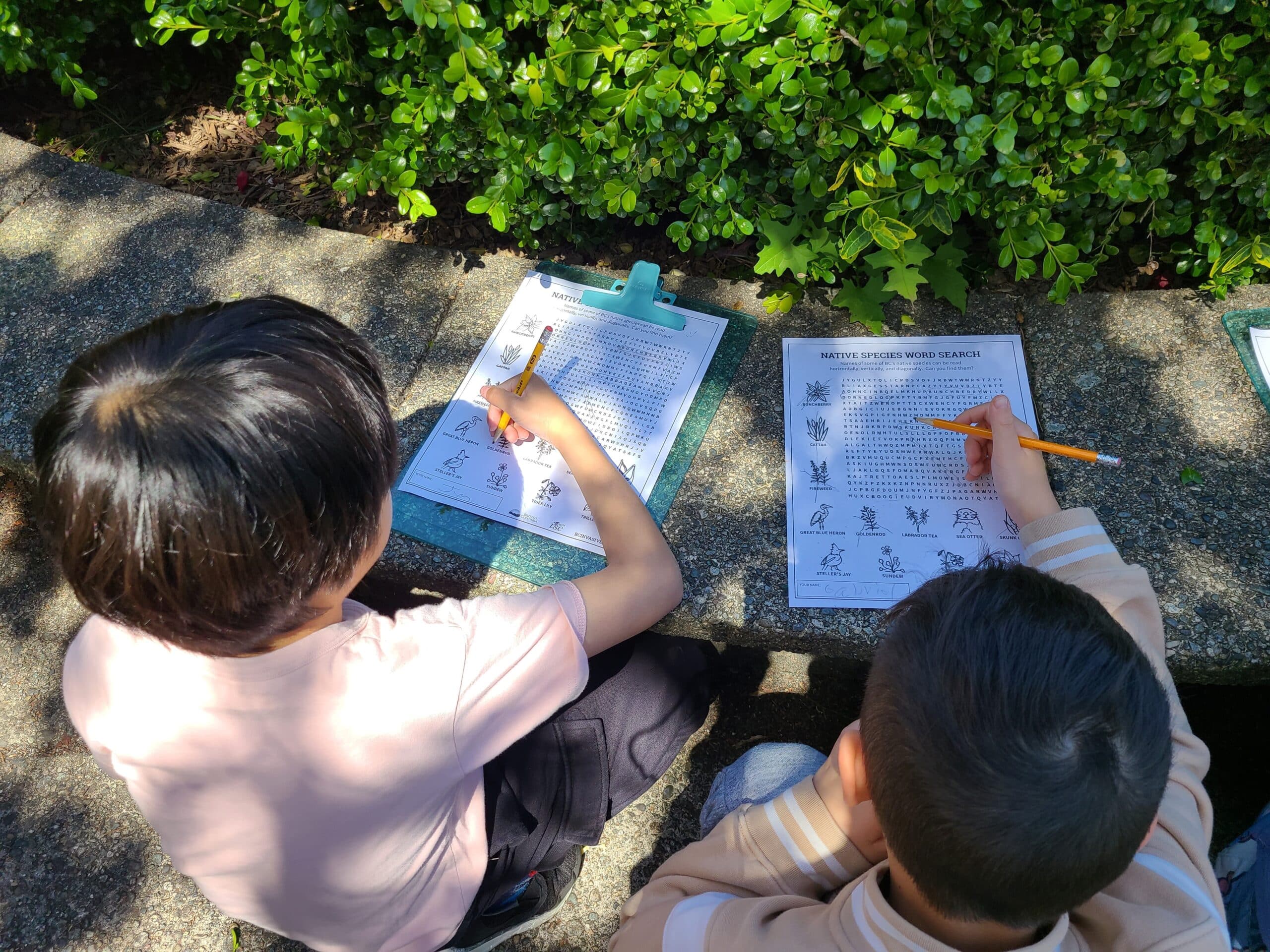

Participants put their new knowledge into action to protect Meighan Creek, its downstream waterways, and the species that call this creek home. After reviewing instructions, the group prepped the site by trimming irises and removing seedheads. They measured and cut lengths of barrier material, secured the pieces together, and carried them to the infestation sites. The mats were secured with pegs and weighted with rocks to help hold them in place.

The benthic barriers will remain in place for over a year to deplete the plants of resources. Under ideal conditions, the plants will not have enough stored energy to resprout next spring. Since this site is along a popular trail, signs were placed to inform visitors about the project and provide contact details should they notice any damage to the barriers. Volunteers will lift the barrier in fall 2026 to assess the results. If needed, barriers will remain for an additional year.

The hands-on experience gained at this workshop increases local knowledge of invasive species and strengthens community capacity to take action in local ecosystems. The workshop demonstrated how community-led efforts can make a meaningful, lasting difference at the local level and set an example for future initiatives.

Thank you to Dr. Catherine Tarasoff, the City of Armstrong, and all our partners and volunteers! The day’s success wouldn’t have been possible without the support of proactive community members and organizations.

This project was funded by a grant from the Regional District of North Okanagan’s North Okanagan Conservation Fund. Thank you for supporting invasive species management in North Okanagan communities!

Ainsley is an Invasive Species Coordinator at ISCBC. You can reach Ainsley at amutrie@bcinvasives.ca

Share