By Lisa Houle | July 23, 2024

You don’t have to go to a zoo to see this invasive reptile. If you live on Vancouver Island, chances are they’re already in your backyard.

Scrambling up rock walls, darting through gardens, basking in the hot, dry heat – this is the time of year you’ll notice invasive European wall lizards.

According to Gavin Hanke, Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at the Royal BC Museum, it may seem like these lizards are everywhere, as the first batch of eggs have recently hatched.

“Wall lizards can get two clutches of eggs a year, and three clutches in warm years. We’ve had the first hatch already this year and expect another hatch in early to mid-August,” said Gavin, noting that lizards are communal nesters, and their clutches range from five to nine eggs. “In time, predators will pick off hatchlings and we’ll be back to a more typical population.”

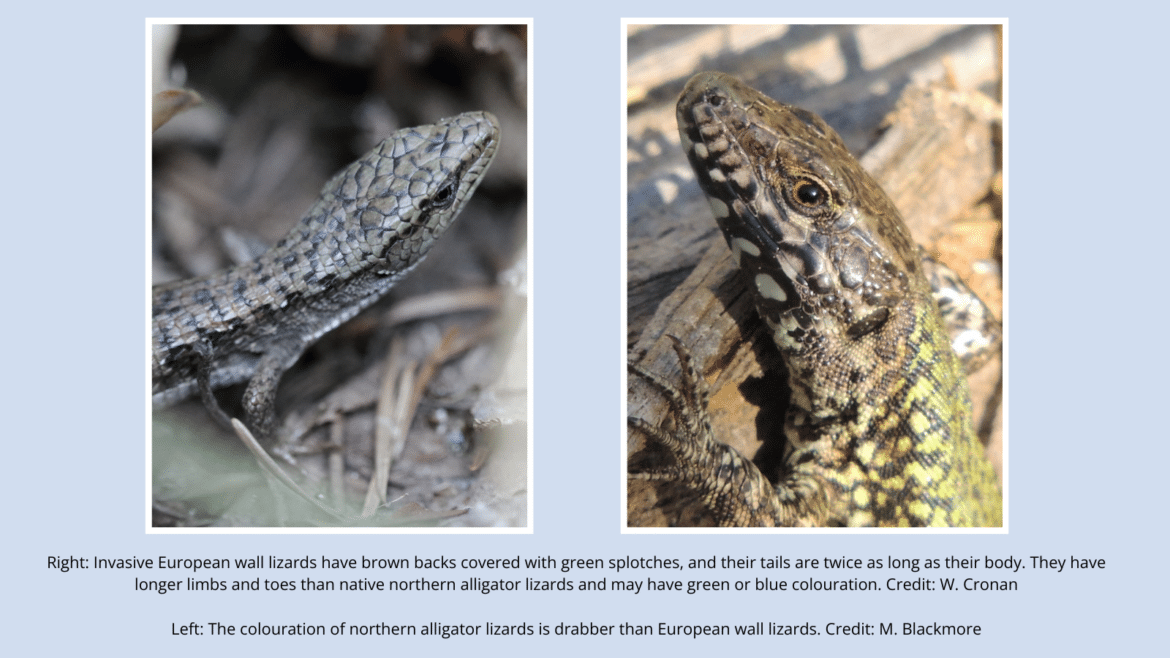

European wall lizards (also known as the common wall lizard) – once captive residents of a small zoo in West Saanich, B.C. – were first released into the wild in 1967. Their population has grown ever since, and so has their range. Like other invasive species, the European wall lizard impacts local biodiversity. They gather in large numbers by nature, leaving little space and food for the native northern alligator lizard and the endangered sharp-tailed snake. They love Vancouver Island’s Mediterranean-like climate, and they eat everything from bumblebees and honeybees, to fruit and berries, even dining out on frogs and young garter snakes. Sometimes they even eat their own young.

“We’ve seen them eating slugs and snails, even dried earthworms. It’s like worm jerky, I suppose. I watched an adult male wall lizard eat a two-centimetre leopard slug – one exotic eating another. We have noticed a dramatic reduction in slugs, ants and earwigs in our garden, which makes some gardeners happy. They also eat berries and ripe wind-fall figs. A lizard up at Sproat Lake was seen chewing the bottom of a tomato – probably for the water held inside,” said Gavin. “They’ve also learned to drink from in-ground sprinkler heads. This is a lizard that has coexisted with people for as long as people have lived in Europe. It’s no surprise they do so well in and around our gardens.”

Gavin’s research isn’t limited to the lab. He has plenty of opportunity for first-hand observations about native and invasive lizard behaviour and populations in his own backyard.

“We must have 60 or more lizards in the garden at any given time. In areas where wall lizards are abundant, I can catch one a minute or more, but I can hunt all day where the alligator lizard is abundant and maybe get 16 to 20 a day,” he said. “Friends have noticed that alligator lizards retreat for the first few years following wall lizards’ arrival, but they return in three to five years to previous population numbers. Having said that, alligator lizards are never as abundant even where they exist naturally in the absence of wall lizards.”

People often ask Gavin if these lizards come with a risk to people or pets.

“I see a lot of emails asking about their poop – it is a mess – but not toxic or dangerous. It can be swept away or hosed off any garden structures. Wall lizards are edible – a friend of mine ate one, though I have no idea why. There’s also no risk to a dog or cat that eats one of these lizards,” he said.

As invasive lizards are much more comfortable around people, you are more likely to encounter them in your yard and garden than our native species. Maintaining a close-cropped lawn and removing basking spots like driftwood, logs and rock walls will make these areas less appealing to them. Doing so also removes their access to food, retreat from predators, and shelter from the frost come winter.

Even then, you might be surprised where you’ll find them.

“They can lay eggs under paving stones, or under the edge of a driveway, in plant pots, and compost bins. Fill cracks in pavement and any retaining walls as it provides a great retreat from danger and the cold. It is amazing to see a perfect rock wall and no lizards, yet a cracked wall in the next garden will be loaded with lizards,” said Gavin. “A shady garden also has fewer lizards than a nice sunny garden. They will climb the side of a house to bask if possible – so make the lower 20-30 centimetres of a house as smooth as possible so lizards cannot climb.

While European wall lizards are invasive in B.C., Gavin is quick to note that not all methods of removal are humane.

“Sticky traps are beyond cruel – and they are not selective. Native species and even birds get trapped if they come down to feed on insects stuck in a trap. I wish sticky traps were banned globally,” he said.

While B.C. grapples with the invasion of the European wall lizard, there are ways to limit their spread.

“Hatchlings and adults are often unknowingly transported to new areas by stowing away on things like vehicles, trailers, hay bales, firewood, garden supplies and other equipment” said Nick Wong, Science and Research Manager at ISCBC. “Populations of European wall lizards have also been found in Vancouver, and one lizard made it to Osoyoos after stowing away in a box of grapes. We can all do our part to stop the spread of invasive species. Before moving anything from areas with known wall lizards, carefully inspect for adults, hatchlings, and eggs. By removing the opportunity for their spread, we can keep European wall lizards from taking over new space from our native species.”

This invasion is a great reminder of the harm that befalls our native species when pets are released in the wild. Please play your part: Don’t Let it Loose!

We greatly appreciate the tales – or should we say tails – shared by Gavin. For more information on the European wall lizard, check out these scientific articles co-written by Gavin here:

European wall lizard origin and recent spread

Lisa is a Communications and Outreach Coordinator at ISCBC. She values a diverse environment and connecting with others about environmental protection. In her spare time Lisa enjoys spending time at the ocean and beach combing for sea glass. You can reach Lisa at lhoule@bcinvasives.ca

Share