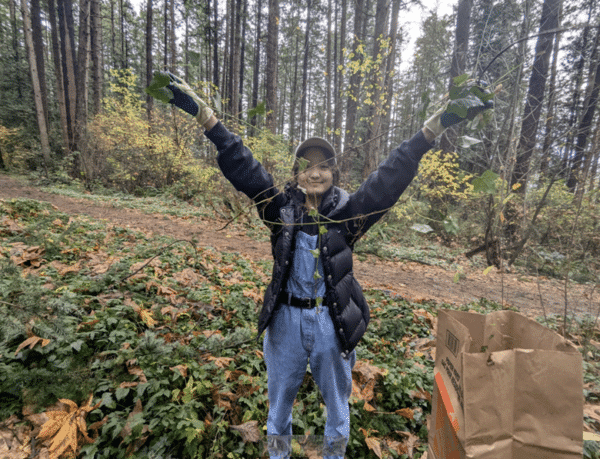

Taylor De Zilva began volunteering with the Youth Network in 2020 and has been actively engaging others in science communication to promote a deeper understanding of the natural world. Recently, she delivered an inspiring presentation at the Annual Youth Summit in January 2022, exploring the importance of science communication and personal connection as when learning about and protecting biodiversity. Taylor is also an avid photographer and uses this unique skill to educate others about science-related topics.

Tell us about how you got involved with ISCBC and the Community Science network!

I got involved with ISCBC and the Community Science network during the fall of 2020. I used to volunteer at the Vancouver Aquarium, VanDusen Botanical Garden and even worked briefly at the UBC Botanical Garden – but when the pandemic occurred, I was forced to move my self-studies and public education online. When I saw an ad on Instagram for volunteering with ISCBC, it was like a dream come true to get back into my old flow of things, even while the pandemic would be unpredictable. Although I may have had a slow start, I have now been doing public education for the past 3 years, and pretty much plan to do it as long as I live, for I really find learning and helping others learn a big joy in my life.

During your presentation at the 2022 ISCBC Provincial Youth Summit, you touched on the concept of “illumination” to create a deeper connection with nature. Can you elaborate on this for those who weren’t able to attend the Summit?

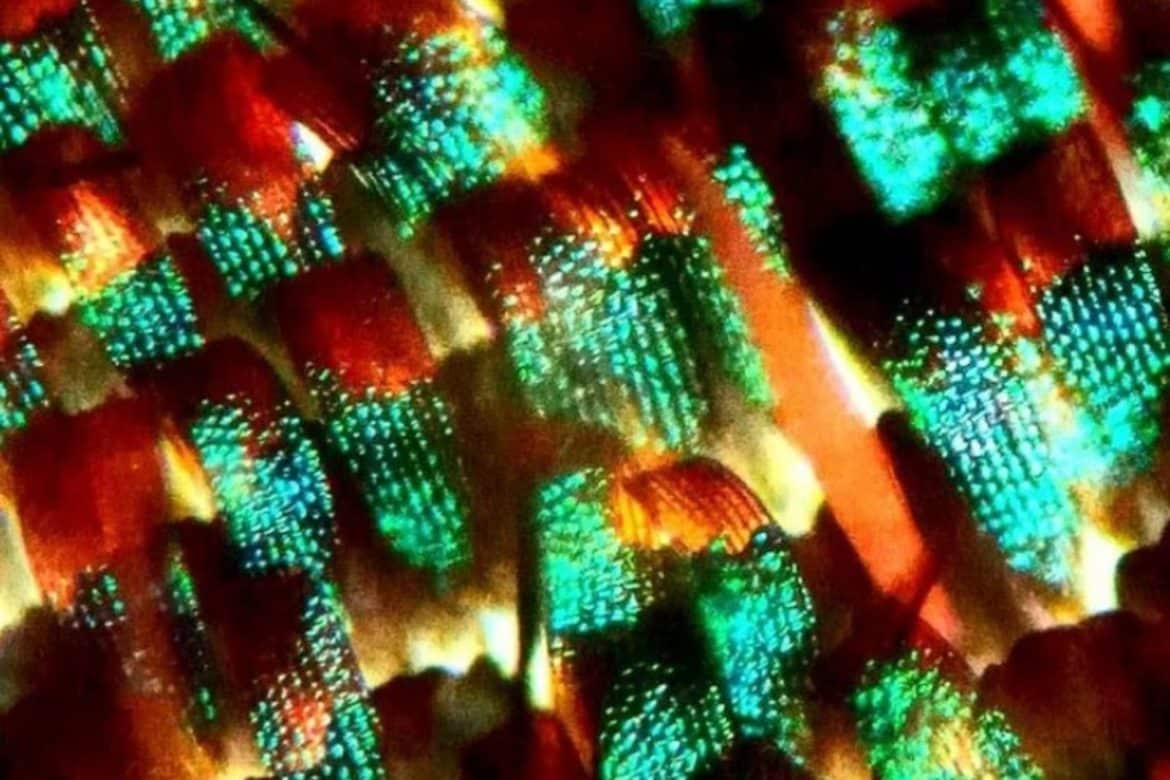

Absolutely! In my presentation, I made an analogy with my hellebore picture and my project, so here I will do just the same. On the left, the photo you see is a Hellebore flower, flowers that are typically quite dull looking in colour, with this variant being composed of whites and dull greens. On the right, the illuminated version of this flower with a black light totally changes our perspective of this little plant. What we see on the black light photo, is what insects see on the ultraviolet spectrum. It’s quite noticeable that the plant is much more vibrant to the insect than it was to us because the insect has evolved to notice and see its relationship with the plant, as some of the most vibrant parts of the flower is where the insect needs to pollinate it.

This is what I want to do with people’s minds, for them to be able to turn on that little backlight in their heads and notice the amazing relationships, connections, and mysteries of nature all around us. We are no different than that insect since ultimately, we are a part of this strange, beautiful and complex world, but in a large respect, we forgot to look outside and see it well enough in the first place.

Your photos are amazing! Do you have any tips for naturalists that are interested in getting into photography?

As a two-pronged response to this one, there is a technical side and an intellectual side. For the technical side – technology is improving at such an exponential rate, I never needed a fancy camera to take most of my photography, I just use a macro lens for near-microscopic things, and the microscope I got off Craigslist for a really good price in amazing condition (I still use my phone for taking the actual pictures even with my microscope).

For the intellectual side – surround yourself with other naturalists! This world is filled with amazing people who are so passionate about helping others see the little ecosystems and habitats all around us that we are also a part of. It was from botanists within the southeast United States that I learned how to use black lights for the ultraviolet spectrum photography that you see. That is another amazing thing too about being interested in invasive species, botany, or biology in general, you can connect with so many people on such a global scale and can have fantastic local impacts on yourself, your relationships with others, and the community

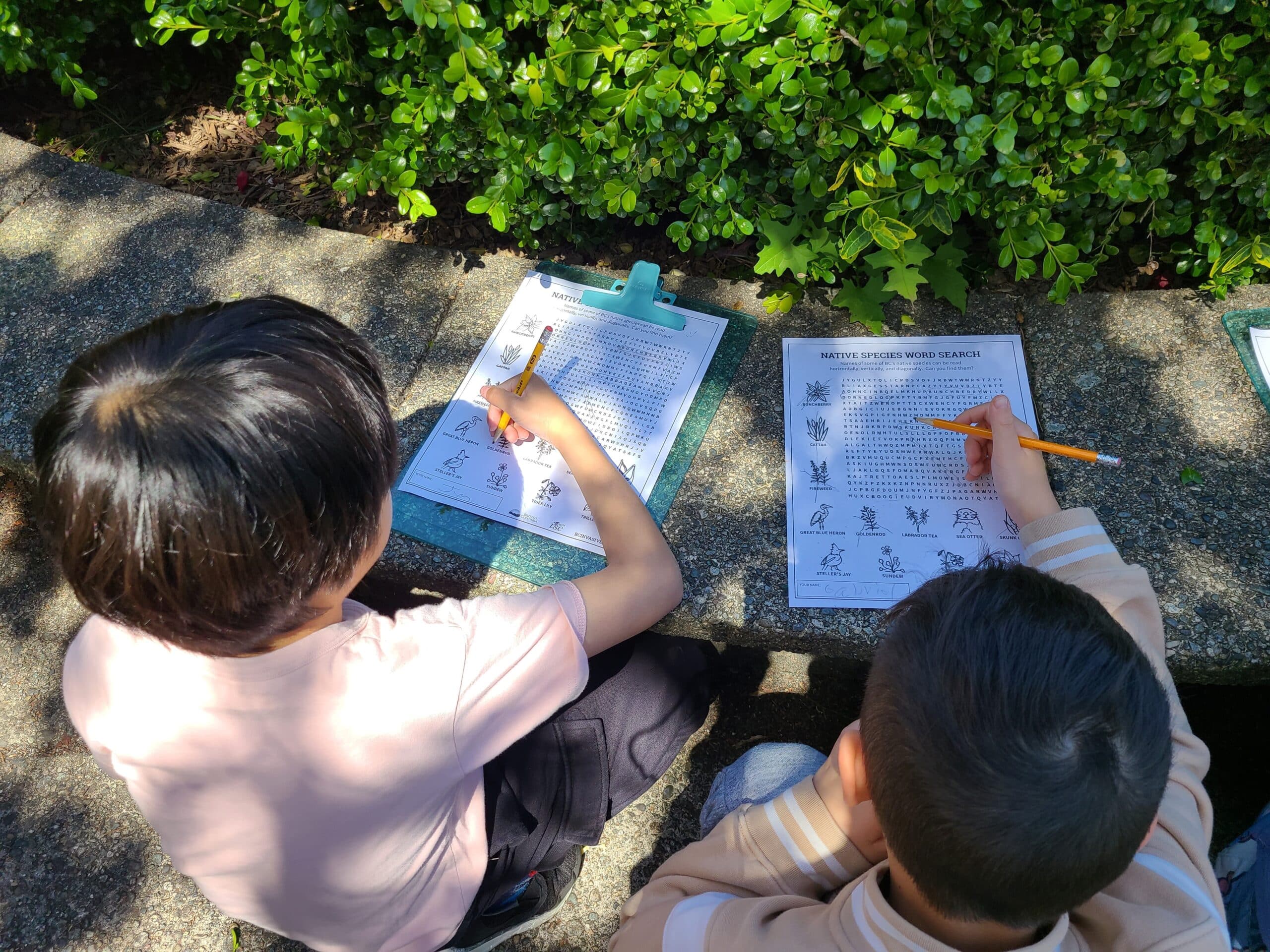

Join Our Community Science Network!

At the Invasive Species Council of BC, our goal is to grow a network of motivated individuals all across British Columbia who are not only informed with knowledge on invasive species identification and impacts but equipped with the tools they need to report new invaders and take action to protect the natural spaces where we live, work and play. Join our Community Science Network today!

Share