By Lisa Houle | May 23, 2024

You’ve identified and reported invasive species. Now it’s time to get to work. Ready, set, remove!

Every species has unique properties and recommended removal methods – following these recommendations will ensure the greatest success. ISCBC staff share some of their most effective strategies when it comes to taking down invasive plants in their own backyards.

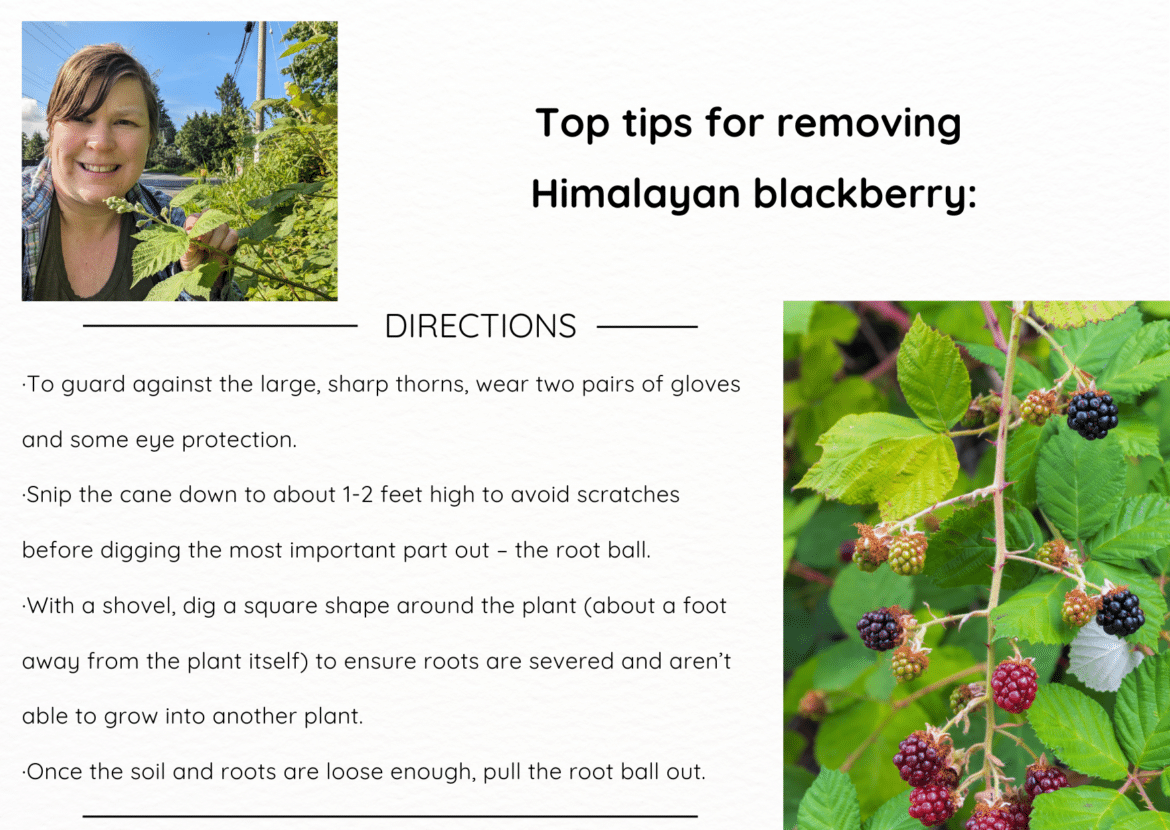

Melanie Apps, ISCBC Youth Engagement Coordinator, started removing Himalayan blackberry in Stanley Park in 2015, later joining the Glenbrook Ravine Ecological Restoration project in New Westminster in 2019.

Although Himalayan blackberry produces edible berries, its trailing vines and sharp thorns crowd out native vegetation and can create a tripping hazard. Easily invading disturbed sites, pastures, roadsides, streambanks, and forest edges, Himalayan blackberry creates dense thickets that can limit the movement of large animals.

“Himalayan blackberry has nasty thorns, and sometimes the tiny ones have gotten stuck in my fingers for days! They can be dangerous if handled improperly,” said Melanie. “Years ago, I was removing some blackberry when another individual working next to me was carrying off one of the canes and its thorns got caught in my hair and snagged my cheek and ear. No serious harm was done, but it was a valuable – and painful – lesson. Part of Melanie’s work with ISCBC has involved working with youth volunteers to remove Himalayan blackberry from various parks around the Lower Mainland.

“Because Himalayan blackberry can grow so dense, every time you remove some you notice the results immediately. As tough of a species as it is to remove, I enjoy seeing the tangible results after just a couple hours of work and knowing that future native species plantings can add diversity to the spot,” said Melanie.

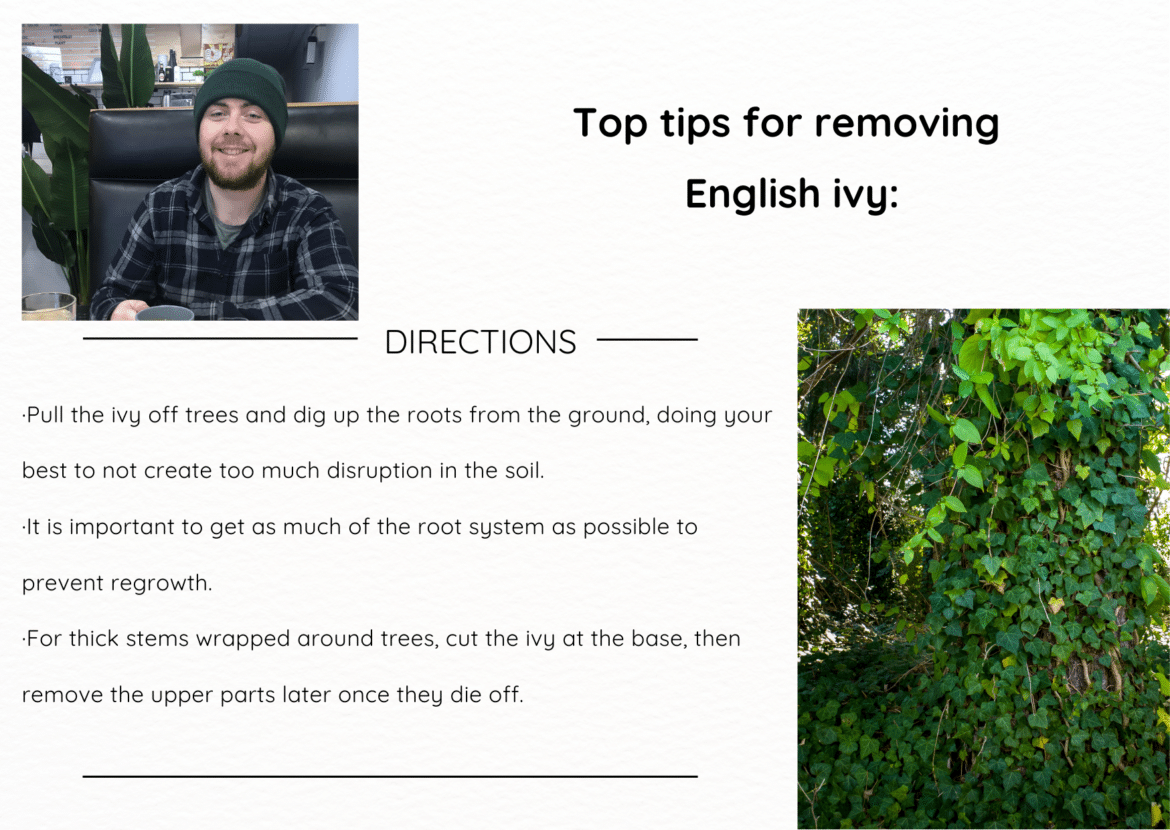

Torin Kelly, Special Projects Lead at ISCBC, has removed English ivy from many urban parks and natural areas in the Lower Mainland. English ivy is a creeping vine that spreads rapidly, creating a dense ground cover that suppresses native plants. It can even climb trees and building walls compromising structures with its roots. The sheer weight of English ivy can cause trees to blow down during windstorms.

“If you take a walk in any park, forest or neighborhood, chances are you’ll find English ivy. Recently I started working from home, and there’s a nice walking path down the street that I try to get to every day at lunch time. The path backs onto a townhouse complex where four massive cedar trees are surrounded by ivy,” said Torin. “Personally, I’ve made it my mission to pull out a little bit of English ivy every day, making sure it isn’t growing up the trees. This is my favourite invasive plant to remove – it is easy enough to manage and can be effectively dealt with through continual manual removal.”

Once English ivy is removed from an area, the difference is striking.

“Native plants and trees start to recover and thrive again. The area looks much healthier and more natural, and it feels good knowing that the ecosystem is on the path to recovery,” said Torin.

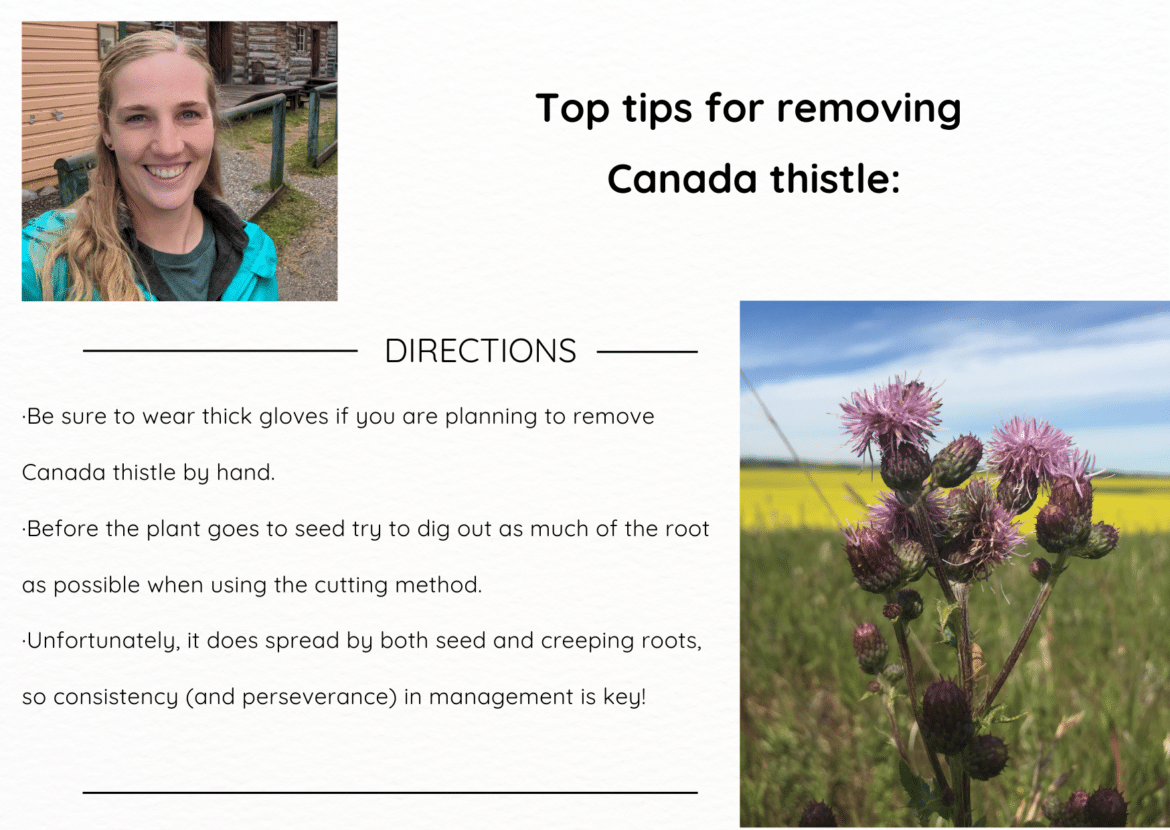

Emma Nikkel, Outreach Coordinator at ISCBC knows how Canada thistle impacts pastures and rangelands in her region by reducing crop yields and production. It’s considered an injurious species due to its sharp spines and in addition to fields and pastures it is commonly found on roadsides, riverbanks, and other disturbed areas.

“Canada thistle is one of the species we are always asked about at outreach events. It is so widespread that it really impacts everyone – from ranchers to home gardeners. I can usually count on finding it and using it as an example species whenever I’m taking school groups on nature walks or hosting a community weed pull,” said Emma.

Emma has helped remove Canada thistle from school yards and as part of a larger restoration project currently underway at Scout Island Nature Centre in Williams Lake.

“Once you’ve removed Canada thistle from an area, it looks and feels so good! Continued management of the area is necessary, so the work is never quite done, but it is very satisfying,” said Emma.

If you find a toxic plant, proceed with caution before attempting removal!

“Find out the best way to remove or control it, but do not risk exposure before knowing the proper way to manage it,” said Dave Ralph, ISCBC’s Senior Manager of Operations. “Report toxic invasive species to your local Regional Invasive Species Organizations. If it is an invasive and/or noxious toxic plant, report it to the provincial government on the Report Invasives App or their website.”

Once an invasive plant is removed do not compost it – bag it and put it in the trash. Some invasive species have seeds or other plant parts that can survive the composting process. Separating green waste stops these invasive plants from spreading.

Happy invasive species removal!

Every year the Province of BC proclaims May ‘Invasive Species Action Month’ (ISAM), recognizing the impact of invasive species on B.C.’s environment, economy, society, and human health. Over the coming weeks, we hope you’ll join us on an engaging and informative journey to learn how to identify, report, and manage invasive species, and get to know some of the easy ways we can all prevent their spread.

Lisa is a Communications and Outreach Coordinator at ISCBC. She values a diverse environment and connecting with others about environmental protection. In her spare time Lisa enjoys spending time at the ocean and beach combing for sea glass. You can reach Lisa at lhoule@bcinvasives.ca

Share