Students are introduced to the deep knowledge and connections that Indigenous people have with native species and the natural world through case studies (salmon, cedar, berries, shellfish, camas, and bitterroot) that include examples of artwork, authentic texts and videos from First Nations in BC. The impact of invasive species is considered in the context of these relationships with the land.

This activity is part of the Lesson “Restoring Connections”, where students discover a deeper connection to the natural world. By engaging in discussion, analysis, and outdoor investigations, students learn about traditional ecological knowledge and how invasive species can impact peoples’ relationship with the environment.

Related Activities

Inquiry Questions

- How did Indigenous people use and manage native plants and animals before European settlement?

- How are people and communities connected to place?

- How does traditional ecological knowledge ensure sustainable uses of natural resources?

- How do invasive species impact culturally important species and traditional land uses?

BC Curriculum Links

Science Big Ideas

- All living things sense and respond to their environment (Grade 4)

- Multicellular organisms have organ systems that enable them to survive and interact within their environment (Grade 5)

- Multicellular organisms rely on internal systems to survive, reproduce, and interact with their environment (Grade 6)

- Evolution by natural selection provides an explanation for the diversity and survival of living things (Grade 7)

Science Content

- First Peoples concepts of the interconnectedness in the environment (Grade 5)

- First Peoples knowledge of sustainable practices (Grade 5)

- First Peoples knowledge of changes in biodiversity over time (Grade 7)

- Local First Peoples knowledge of climate change (Grade 7)

Science Curricular Competencies (All Grades)

- Identify First Peoples perspectives and knowledge as sources of information

- Experience and interpret the local environment

- Express and reflect on personal, shared, or others’ experiences of place

Social Studies Big Ideas and Content

- Interactions between First Peoples and Europeans led to conflict and co-operation, which continue to shape Canada’s identity (Grade 4- Big Idea)

- First Peoples land ownership and use (Grade 5- Content)

Materials

Documents to Download

Everything is One – Case Studies

Background

The Indigenous people that live in the place now known as British Columbia have deep knowledge and cultural connections to the lands and waters. Before colonization, Indigenous people relied on the land for everything they needed in life! This includes foods, medicines, and materials used to build homes, to make clothing, baskets, canoes, hunting and fishing tools, and those used in spiritual ceremonies. Many people were able to recognize hundreds of different types of plants. They knew where they grew best, what pollinated them, what animals would eat them or nest in them. They know how plants could be used by people , including if they were edible or poisonous, if they could be used as medicine, or other useful properties. In addition to being important sources of materials and foods, many plants and animals have important cultural, spiritual, and traditional significance.

People understood that they were intricately connected to the great web of life, that everything is interconnected and “Everything is One”. This concept of interconnectedness is embedded in how people interacted with the natural world. It is also rooted in language.

Protocols and ceremonies took place to ensure that all living things were treated with respect and to guarantee an “honorable harvest” (as described in Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, Milkweed Editions, 2013). Permission was respectfully asked, prayers were given to the plants and animals before taking anything from the lands or waters, and there was a fundamental gratitude for the gifts. Only what was needed was taken and nothing was wasted. People understood that this was essential in order to have enough for their community, their children, grandchildren, and generations to follow. Certain people in the community were “guardians” who closely monitored the health of the resource to make sure that it was managed properly. And people knew the subtle signs and signals from the land that indicated seasonal changes and when it was time to harvest.

Plants and other resources were not simply “gathered”. Although certain plants or animals may have been abundant, in many cases this was due to the fact that people were actively managing the habitats in complex and intricate ways that promoted desired species. And as a result, this management benefitted many other native species and often increased local biodiversity!

First Peoples’ land use and traditional ecological knowledge have suffered tremendously due to residential schools, laws banning traditional management and harvest practices, and other impacts of colonialism. Connections to the land remain strong, however, and there are efforts to resurrect traditions. Today, the spread of invasive species is an additional challenge that impacts traditional land use, such as by blocking access to harvest sites, causing changes in ecological processes (such as increasing erosion or fire frequency), and by causing a decrease in abundance and diversity of native species. By understanding traditional ecological knowledge, students will develop a stronger connection to place. Taking action on invasive species is one way to help restore connections.

For general information on invasive species read Background on Invasive Species for Educators and Invasive Species that Impact Indigenous Communities.

Preparation

Read the Background Information and Case Studies. Download Case Studies that you will focus on with your students.

Procedure

Part 1. Everything is One

Have the students imagine a time from the past. You could have them close their eyes and have them visualize what it would be like to live in a time before the internet and electronics, before grocery stores, pharmacies, and shopping malls. Have them imagine where they would look for and gather food. Ask them if they were in the forest would they know what plants could be eaten? Would you know what time of year you could find the animals and plants you needed to survive? What would happen if you felt sick or got injured? Would you or someone in your family know what plants could help you? Encourage sharing of students’ own traditions and their connections to and knowledge of the environment.

Present the phrase “Everything is One” and ask the students what they think it means. Tell them that it is a concept that is expressed in many First Nations languages. For example:

- Nuu-Chah-Nulth (Central and Northern Coastal BC) say Hishuk ish ts’awalk, “everything is one and all are connected”

- Haida (Haida Gwaii) say Gina ‘waadluxan gud ad kwaagid, “Everything depends on everything”

- Secwepmc (Shuswap, South-Central Interior) say Kweseltnews “We are all family”

(Secondary Science First Peoples Teacher Resource Guide, FNESC/FNSA 2019 http://www.fnesc.ca/sciencetrg/)

Have students discuss the phrase “Everything is One” as a class or in small groups. Explain that interconnectedness is a fundamental part of First Peoples’ worldview. Ask students to come up with examples of interconnectedness in the natural world. Provide them with discussion questions, such as:

- How are you interconnected with other species in the environment?

- If one lives with the phrase “Everything is One” in mind, how does it impact how one interacts with the natural world?

- If you think of other beings (animals and plants) as having a vital role in the web of life, or having awareness, intelligence, or a spirit, how does it affect how you might use or harvest that being?

Optional: Build an Ecosystem Web using a ball of rope or yarn to demonstrate the interconnectedness between all organisms.

- Cut out images or make labels of different species (a diversity of native species from the small to large, microorganisms and invertebrates to mammals) and non-living things (sun, soil, water, rocks, air, etc) found in the environment in your region.

- Give everyone their “identity” and have them gather in a large circle. Have them introduce themselves to each other.

- Begin by giving one student the ball of yarn. Ask them to hold the end of it and identify another student that they are somehow connected to. Consider the food chain (what eats the animal and what it eats) and its habitat needs (such as where it nests, shelters, or spends part of its life cycle). For example, the sun provides energy to the maple tree; the squirrel eats the maple seeds, the owl eats the squirrel, the fungus decomposes the tree, etc.

- While holding the end of the yarn, the student describes how they are connected to another student and passes the ball of yarn to that person, who then identifies another student that they are connected to.

- Discuss the relationships found between each connection and continue passing the yarn until everyone is connected in a giant web. Discuss how the web represents that all things in natural systems are interconnected and interdependent. Consider what would happen if one species were removed from the web (it would unravel). Discuss the threats to some of the species in the web (such as habitat loss or invasive species impacts) and ways that the web can be protected (conservation actions, local organizations and stewardship activities).

Part 2. Case Studies

Break students into up to small groups and assign each one a Case Study (Camas, Salmon, Clams, Berries, Cedar, Bitteroot). Each group should examine the content in their Case Study, including the text, images, and videos.

Help guide student discussion and analysis by providing some questions, such as:

- What is the significance of this plant or animal to First Nations people? (How is it used, what does it provide to people, etc.)

- What knowledge do people have of the species and of its relationship with other species in its habitat? (Interconnectedness)

- How did First Nations people show respect to the species? How did they ensure that it would be harvested in a way that it would be available for future generations?

- For images (art, photographs): What is this an image of? What does the image reveal about the relationship between people and the plant or animal?

- What are some factors that threaten the native species and/or the relationship between First Peoples and the species or its habitat? How could invasive species have an impact?

Each group could share their Case Study to the rest of the class, in a format such as in an oral presentation, a video, a blog, poster or art work, or slide show.

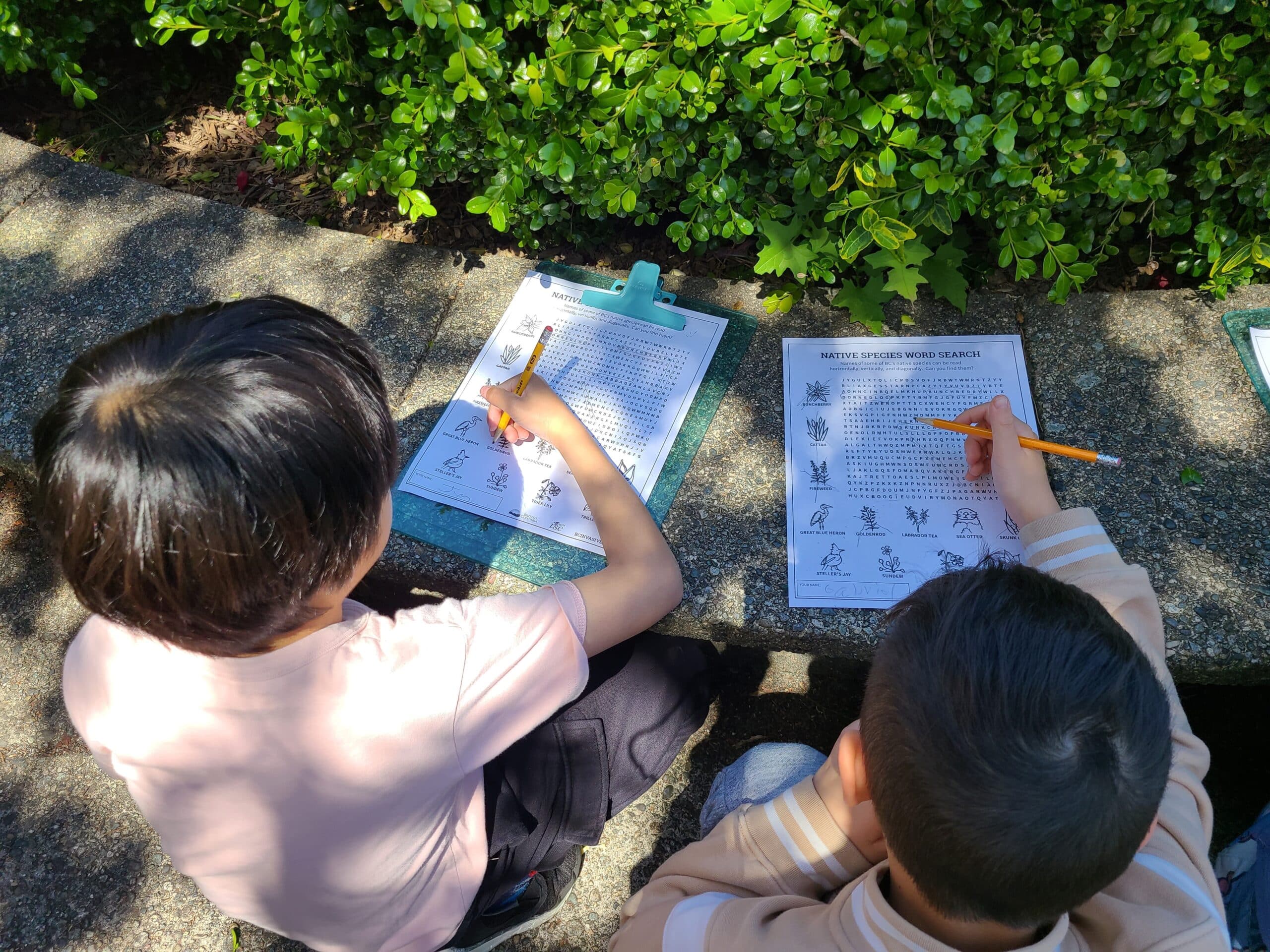

Part 3. Get Outdoors!

Go outdoors to experience the species and habitats that you learned about in the Case Studies. If that isn’t accessible, explore the schoolyard or a nearby green space with new perspectives, noticing things that may have been overlooked on other visits and considering how everything is connected in the ecosystem. Some activities to do on site could include closer observation using magnifiers or binoculars, nature sketching, journaling or taking photographs. Students could also use field guides or ID apps (such as iNaturalist or SEEK) to identify common species and learn if they are native, non-native or invasive.

Learn how to identify and report invasive species here at bcinvasives.ca/report. By reporting invasive species you are helping to take care of and protect biodiversity.

Share with us!

We’d love to have your feedback and see photos of your students’ learning and participation in this activity. Send to education.lead@bcinvasives.ca for the opportunity to win resources and have your class have a virtual visit with an invasive species expert!

Extensions

- Learn about traditional ecological knowledge of a resource or habitat in your region. See the Resources section for some possible sources of information or consult with local communities and First Nations liaisons within your school district.

- Learn how to say some words or expressions about animals or plants in a First Nations language from your region. Is there an expression about interconnectedness or “Everything is One” in that language? A useful website is https://www.firstvoices.com/

- Interview a First Nations elder. Activity description here: https://bcinvasives.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Activity_Sheet_-_Past_Present_Future-1121.pdf

- Create your own field guide. Activity description here: https://bcinvasives.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Activity_Sheet_Indigenous_Field_Guide-1121.pdf

Additional Resources

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

- The Boreal Herbal: Wild Food and Medicine Plants of the North. Beverly Gray. Aroma Borealis Press, Whitehorse, 2012.

- Food Plants of Interior First Peoples. Nancy J. Turner. Royal BC Museum, 1997.

- Ktunaxa Ethnobotany Handbook, ‘?a-kxam̓is q̓api qapsin’ (All Living Things).

- Pacific Northwest Plant Knowledge Cards, Strong Nations.

- Saanich Ethnobotany: Culturally Important Plants of the WSANEC People. Nancy J. Turner and Richard J. Hebda. Royal BC Museum, 2019.

- Science First Peoples Teacher Resource Guide, Grades 5-9. 2016, First Nations Education Steering Committee and First Nations School Association.

- Staying the Course, Staying Alive- Coastal First Nations Fundamental Truths: Biodiversity, Stewardship and Sustainability. 2009. Frank Brown and Y. Kathy Brown (Compilers). Biodiversity BC. Victoria, BC. 82 pp.

- To Fish As Formerly- A Story of Straits Salish Resurgence (WSANEC Reef Net Fisheries). Legacy Art Gallery, University of Victoria.