By Diane Watson | November 5, 2025

Bats are among the most vital yet misunderstood animals in British Columbia. As nighttime insect hunters, they play a quiet but powerful role in maintaining balance – a single brown bat can devour thousands of mosquitoes or crop pests in a night. Despite this ecological importance, many bat populations across North America are declining due to human-driven pressures. Habitat loss, disease, and climate change are well-known causes. Another danger is emerging invasive species that disrupt, entangle, or infect bats where they live and feed.

Bats reproduce slowly, typically giving birth to just a single pup each year. This low reproductive rate means their populations recover slowly after losses. Most species in B.C. feed exclusively on insects, roosting by day in trees, cliffs, caves, or old buildings before emerging at dusk. They are highly sensitive to disturbances, especially during hibernation or breeding. Because they depend on specific roosting and foraging habitats, they are particularly susceptible when those areas change.

While bats have evolved to survive natural predators and harsh climates, they’re poorly equipped to handle rapid ecological change. The arrival of invasive species, including plants, animals, and pathogens, has introduced new threats that many bats haven’t adapted to.

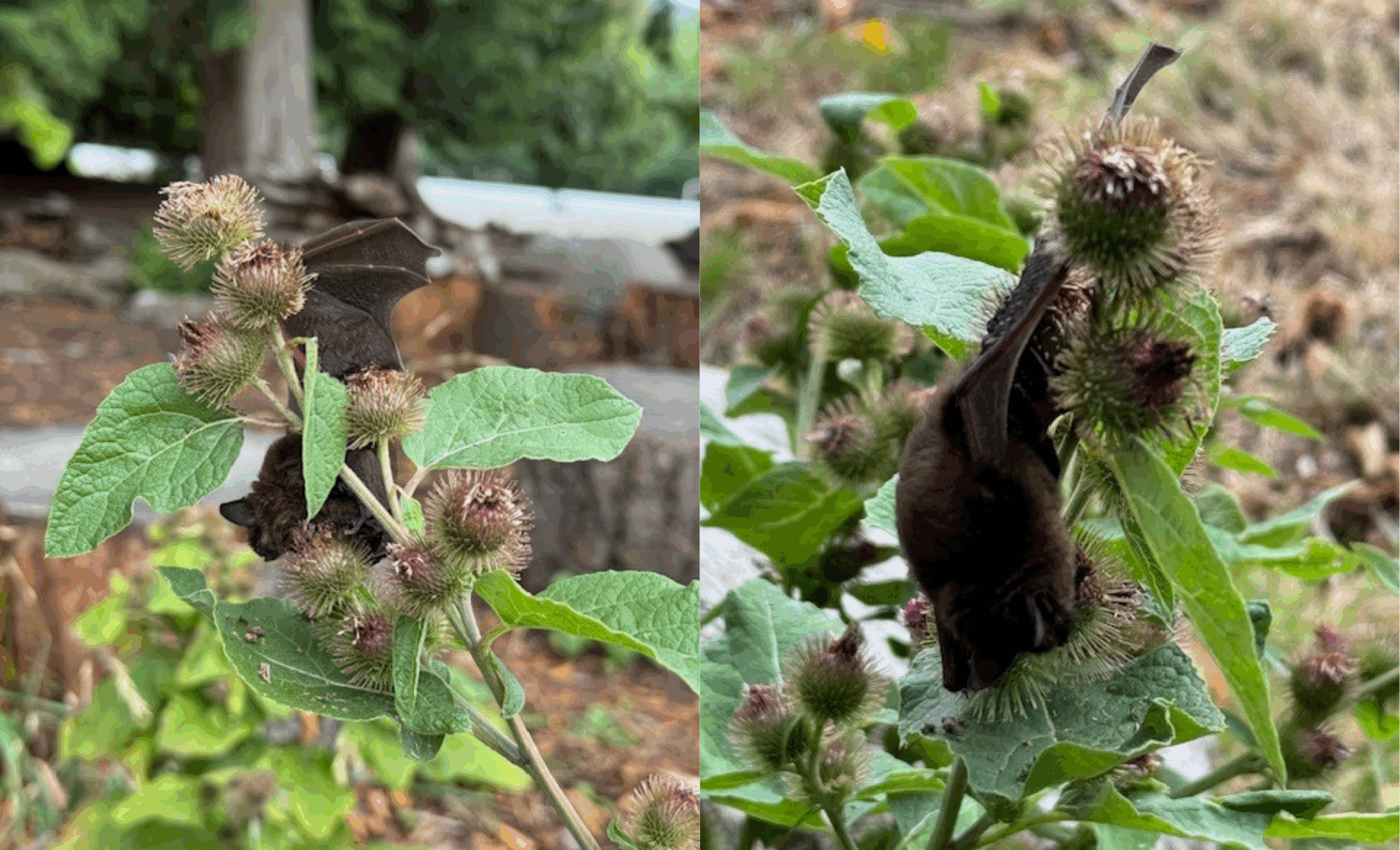

Burdock, a hardy weed originally from Europe and Asia, has become a threat to bats across North America. It thrives in disturbed soils along roadsides, trails, and the edges of fields and waterbodies where bats often hunt for insects. They produce clusters of burrs with stiff, hooked bracts that latch onto passing animals to spread their seeds. Unfortunately, these same hooks can snag the thin, flexible skin of bat wings. Once caught, bats often struggle to free themselves and can die from exhaustion, starvation, or exposure. Because these incidents often occur out of sight, their full impact is unknown, but field reports suggest entanglement is not rare.

Managing burdock before it goes to seed is one of the best defenses. Removing plants by the root, cutting seed heads, and disposing of them safely prevents further spread. Avoiding dense stands of burr-forming weeds when installing bat boxes or creating habitat areas can also reduce accidental contact. The broader issue goes beyond one plant. Invasive vegetation can change bat foraging areas, reduce insect diversity, and create dense growth that limits the open spaces bats need to fly and feed.

If burdock presents a mechanical hazard, a more devastating biological threat has been spreading across the continent for over a decade. White-nose syndrome (WNS) is caused by a cold-loving fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, originating in Europe. The fungus invades the skin of hibernating bats, particularly their wings and muzzles, disrupting their metabolism and causing them to wake repeatedly during winter. Each arousal burns through crucial fat reserves, often leading to dehydration and starvation before spring arrives.

Since its discovery in New York State in 2006, the fungus has wiped out millions of bats across eastern North America, driving some species to near extinction. The pathogen has already been detected in nearby Washington State and poses a significant risk to bats in B.C. As of recent reports, the province remains free of confirmed cases. Scientists and wildlife agencies are closely monitoring the situation and using public reporting programs to detect early signs of infection.

White-nose syndrome spreads mainly through bat-to-bat contact but can also be carried by contaminated clothing or gear. Simple precautions, like cleaning and disinfecting boots, gloves, and caving or climbing equipment, can help slow the fungus’s spread. Because the pathogen came from overseas and has no natural controls here, it’s considered an invasive disease and one of the most significant wildlife diseases in modern North American history.

Cats

Some invasive pressures start close to home. Domestic cats, though beloved companions, are an introduced species that poses serious risks to native wildlife. Bats occasionally fall victim when they roost near homes or hunt insects under outdoor lights. Cats’ natural hunting instincts make them formidable predators, and even well-fed pets can injure or kill bats that venture too close to the ground.

Keeping cats indoors at night, using enclosed “catios,” or supervising outdoor time helps protect both bats and birds. This simple shift in pet care prevents unnecessary wildlife deaths while keeping cats safer from cars, disease, and predators.

Gardens

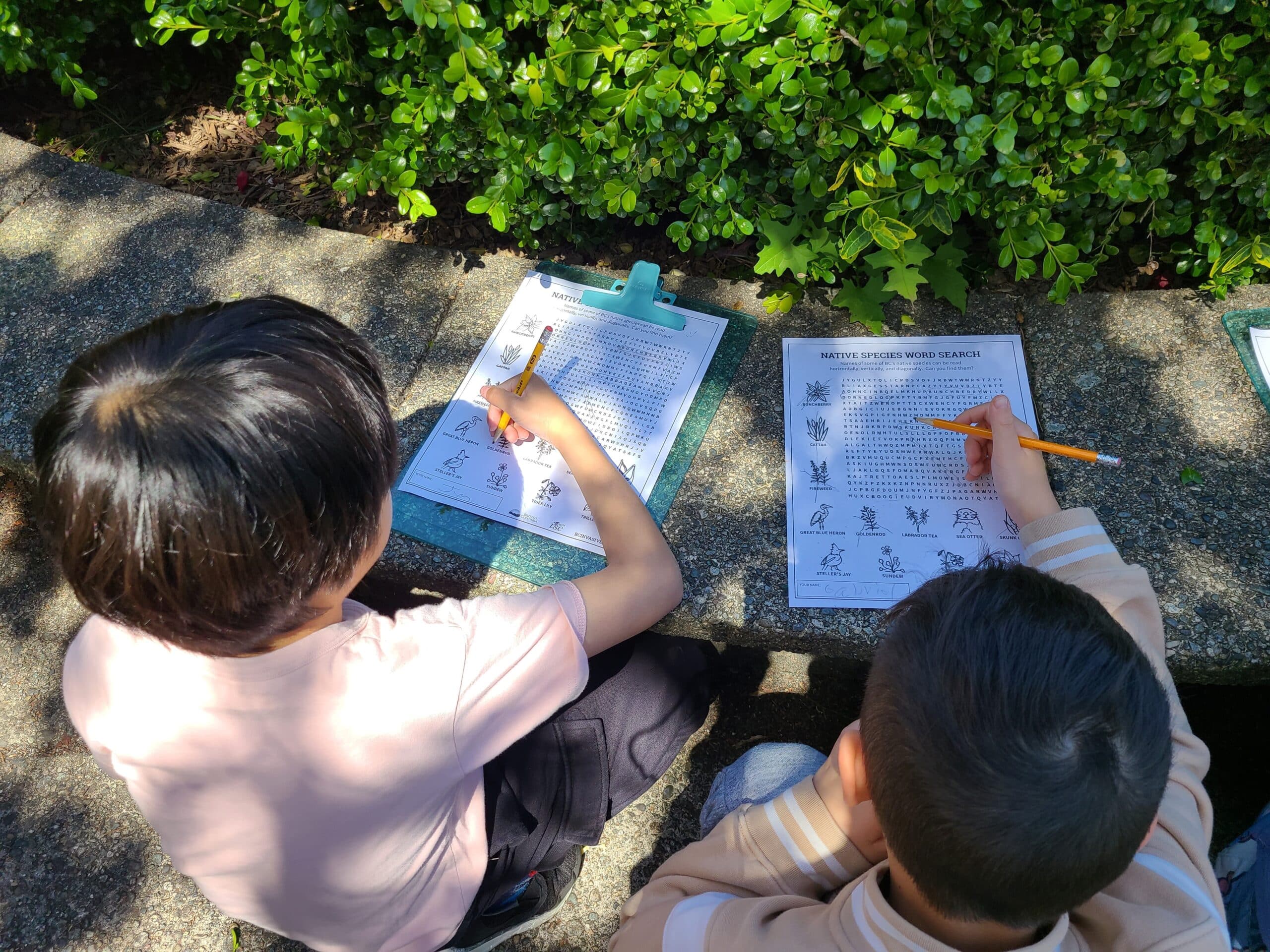

People who enjoy gardening can also play a positive role in bat conservation. Creating bat-friendly gardens, featuring native flowering plants that attract night-active insects, provides safe feeding zones and supports natural food webs. Native plants are adapted to local climates and insect species, while invasive ornamentals can outcompete them and reduce insect abundance. Gardeners can also install bat boxes, provide clean water sources, and keep bright lights to a minimum, as artificial illumination can deter nocturnal foraging. Make sure to check the ‘Grow Me Instead‘ guide to learn about native or non-invasive alternatives.

Big Picture

Bats have been evolving for over 50 million years, yet many of their greatest threats have only emerged in the past few decades. Invasive species, whether a burr-covered weed, a microscopic fungus, or a household pet, represent new pressures in ecosystems already stressed by urbanization and climate change.

Protecting these nocturnal mammals isn’t just about saving one group of animals. It’s about safeguarding an important ecological service that benefits us all. Each action – removing a patch of burdock, cleaning hiking gear, or keeping a cat indoors – adds to a safer landscape for bats and the ecosystems that depend on them.

Diane is a Special Projects Coordinator at ISCBC with a background in forestry and ecological restoration. She is passionate about working collaboratively to protect natural ecosystems and empower communities to take action. Outside of work, Diane enjoys snowboarding, hiking, camping, and exploring nature with her rescue dog, Benita. You can reach Diane at dwatson@bcinvasives.ca

Share